Vol. xxii #1

March, 2001

The Beauty of their Sorrow

|

tlf news |

Vol. xxii #1 |

March, 2001 |

The Beauty of their Sorrow | |||

| Nor in Eligschylus nor

Dante, those stern masters of tenderness, in

Shakespeare, the most purely human of all the great artists, in the

whole of Celtic myth and legend, where the loveliness of the

world is shown through a mist of tears, and the life of a man is no

more than the life of a flower, is there anything that, for sheer

simplicity of pathos wedded and made one with sublimity of tragic

effect, can be said to equal or even approach the last act of

Christ's passion. -Oscar Wilde: De Profundis |

In the months of February, March and April, while the fiercest tropical heat casts a soporific spell over the north coast of Honduras, teatro la fragua focuses its internal rehearsals and its workshops on the work The Assassination of Jesus. The work forms part of a project baptized with the name The Gospel -- Live!, which teatro la fragua has been presenting and polishing continuously since 1984. This biblical theatre project has its roots in the medieval theatre; it is a descendent, transplanted to Honduran soil, of the theatrical traditions which sprang up in Europe in the tenth century. |

||

The collapse of the Roman Empire also meant the death of the theatrical tradition invented by the Greeks. In the Middle Ages theatre experienced a second birth which was attended by midwives whose cassocks reeked of conventual incense. The medieval theatre's birth was intimately linked to the rites of the Catholic Mass and the chanting of the Liturgy of the Hours. These two rituals (along with the wars, the plagues and the poverty) were the spinal column which governed the lives of medieval towns. Church buildings were transformed into theatres, providing a space for the development of theatrical traditions which recreated and reinforced the fundamental nuclei of the Catholic faith: the women's visit to the sepulchre on Easter morning, and the central episodes of the Passion and the birth of Jesus. Throughout that epoch, considered "dark" by many of the "enlightened," the monastery libraries were the place where the cultural tradition of the ancient world survived. The monks chanted the office and cultivated the land; they also dedicated many hours to the translation and the copying of ancient manuscripts. |

||

Rehearsals begin at 8:00 a.m. with a routine of physical exercises which lasts half an hour. The medieval monks failed to understand the importance of the body, which they considered a wild beast and which they treated as such, silencing its cries with whips and hair shirts. To the contrary, the muchachos of la fragua understand very well that the body is the principal instrument with which they have to work; for that reason, they train it, exercising it daily to awaken its energy and to learn to control it. After the physical exercises there is another half hour for breathing and voice exercises. The goal is to learn to breathe well and to coordinate the breathing with the voice and with bodily movements. la fragua under no circumstances recurs to microphones to amplify the voice: the force of the theatre resides in the direct and personal communication between actors and audience. Theatre cannot admit the distancing which is the very nature of the electronic media. The body, by its very

strength and actions, has sufficient power to

alter the nature of things more profoundly than the spirit, in

speculation or in dreams, will ever achieve. |

||

It is now 9:00 a.m. and the actors of la fragua rehearse the music and the songs of the piece. They start with warm-up exercises and scales, and then move on to the songs themselves. At 9:30 they gather around the director, who gives them a few general indications of the goals of the day's work; then the scene rehearsals begin. teatro la fragua was not interested in just putting on plays, but in discovering a style of theatre that would stimulate the creation of a theatrical tradition among the people. With this goal in mind, a few years after its founding, the teatro adopted the formats of medieval theatre; these were seen as the most practical model to adapt to the characteristics of the Honduran reality. There is no corner of the country so isolated that it doesn't have a small church. The life of the people flows with the rhythm of the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church, and the churches are the principal gathering place of the population. Besides, Honduras' social setting bears a considerable similarity to that which existed in the Middle Ages: large portions of the population have no access to education or to any form of cultural pastime. Cutting-edge discoveries like the Internet, cloning, the human genome - topics at the center of attention in the life of other countries - are totally unknown to a majority of the population. In this context, the village priest and the Bible have been the principal sources of culture and education in large portions of the Honduran countryside. |

||

In the popular celebration of Holy Week there are abundant theatrical elements. These are not theatre as such, but they provide the basic tools of a real theatrical expression: there are narrators, there are symbolic characters present in statuary, there are processional movements and there are "sets," music and costumes prescribed for the occasion. On Good Friday in the villages and cities the reenactment of the Way of the Cross is a strong tradition. The Stations are located along the path that leads from one village to another. In some cities the streets are covered with colorful carpets of dyed sawdust which depict the episodes of the Crucifixion. The people process under the blazing sun, chanting a mournful "Have mercy on your people, Lord". |

||

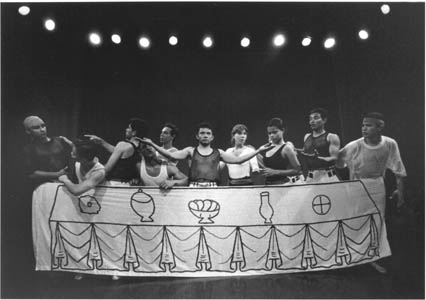

The celebration of Good Friday begins on Thursday night, when the whole village processes in silence through the streets, accompanying the arrested Jesus to the rhythm of a huge chain striking the street (because Jesus is in chains). The traditional religious folklore of Good Friday prohibited, under pain of severe divine punishment, the realization of any kind of festive activity which would point the spirit toward joy or diversion. (It is still the only day of the year when EVERYTHING shuts down). In the villages in the mountains, grandmothers scolded children if they caught them playing or laughing, because Jesus was dead. And they struck fear into the children's hearts by recounting the myths of children whom God had changed into monkeys or fish for playing in the trees or the streams on Good Friday. In the afternoon the whole town accompanies the bier with the remains of Jesus in the burial procession, and on one or another street you see a rag-doll effigy suspended from a tree: Judas Iscariot hanged after selling out his Master. The rites of Good Friday infiltrate even the kitchen. These are the days of existing on fruits pickled in honey which are generously offered to any visitor, and the houses are filled with the aromatic vapors of soup made from dried fish. Taking off from the ancient

tradition of representing the Gospel

within the context of the rite of the Mass, the group has achieved

a very personal style and esthetic. The concept of the production

is of a series of "living

paintings" which are based on the

paintings of Da Vinci, Bruegel, El Greco, and numberless other

masters of religious art. More than playing characters, the actors

evoke situations, and each of the actors in turn takes the role of

Christ. The costumes are contemporary, giving the story a

contemporary relevance which allows the spectator to

concentrate on the story's

contemporary meaning -- and arrive at

the conclusion that he sees in front of him a blue-jean

Jesus. |

||

|

The Assassination of Jesus has taken these traditions of popular Honduran religiosity as its starting point, but has grafted on branches from other traditions of the Christian West which spring from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and beyond. The music takes off from the merengue and salsa of the Caribbean coast, but passes through the Bach Passions and even two renaissance pieces sung in Latin, just as the monks sang them when they chanted lauds or vespers. The incorporation of Latin serves to highlight the most solemn scenes, such as the entrance to Jerusalem and the moment when the actors form the living painting of the Last Supper. But on another level, a large portion of the audience at any performance of The Assassination of Jesus are young people for whom it is a good experience to realize that there was a time when Latin, which has now joined the inventory of retired languages, was an important, living tongue which was highly influential in the construction of European culture and one of the roots of our own cultural identity. The visual style of the piece is inspired by medieval and renaissance paintings. teatro la fragua uses these paintings as a visual reference for the stage compositions and to create a plastic image by which an audience unaccustomed to listen closely to linguistic details can understand the action on a purely visual level. At the same time, following the cue of the Old Masters, the story is situated in a present-day Honduran village: this is what gives special life to the Gospel. |

|

A theatrical work should not limit itself only to the expression of the culture from which it springs; it is important that its message have the capacity to dialogue with other cultures. One of the most gratifying experiences of teatro la fragua was the presentation of The Assassination of Jesus in a medieval Spanish church during the tour of Spain in 1998. The Spanish audience experienced the warmth of a message in which they could hear echoes of their own medieval Spanish theatrical tradition, seasoned with the beauty and force of Honduran and Latin American religious and cultural traditions. By its very nature art has the obligation of showing us the sources from which our own identity springs, so that we can recognize that our differences are accidents of a common geography shared by all, in which the distinct branches depend on the same trunk and are fed from the same roots. |

||

teatro la fragua reproduces and propagates these theatrical techniques by means of workshops which bit by bit are building an authentic theatrical tradition. The teatro reaches to the most remote regions of Honduran and Central American geography. In these workshops the actors teach groups of young people the same techniques which teatro la fragua employs for its own mountings of The Assassination of Jesus and Navidad Nuestra. In the course of a long week-end of intensive work these young people, mostly campesinos with little or no schooling, learn the basic techniques for dramatizing the Gospels. Each of the fragua actors works with a small group, and to each group is assigned the mounting of one of the scenes. The workshops include sessions of physical exercises, breathing and reading exercises and music. The latter is rarely a major problem because almost every village can count on someone who regularly provides the guitar accompaniment at Mass. During the Sunday morning Mass the actors make their debut, presenting to the faithful the scenes they have been working on. Then, during Holy Week, the different groups come together to present the whole story of The Assassination of Jesus in each of their villages in turn, at this point without the help of their fragua directors. This is the foundation of a theatrical tradition which, by means of simple and accessible techniques, sparks the creativity of those rural sectors normally marginalized from the centers of culture and education. |

||

In the history of all cultures, religion has been the root from which art has sprung. The artist has always been the genial interpreter of that invisible mystery which hides the gods from the profane view of mortals. Artistic expressions have awakened pity or terror, commitment or doubt, and have been a major factor in the humanization of believers and nonbelievers, at times in the face of the fury and persecution of both civil and religious authorities. The artist's vision translated into theatre, music, painting or any other artistic expression has also reflected the vision of God, in whose eyes humanity can contemplate the truth of its condition. teatro la fragua understands clearly this mission, and is confident that one day its efforts will help bring into being a better and more worthy human race, a more compassionate humanity, tolerant and solidary, human beings worthy at last of the name. |

||

|

Christ's place indeed is with the poets. His whole

conception of

humanity sprang right out of the imagination and can only be

realized by it.... There is still something to me almost incredible

in the idea of a young Galilean peasant imagining that he could

bear on his own shoulders the burden of the entire world...: the

sufferings of those whose names are legion and whose dwelling is

among the tombs: oppressed nationalities, factory children,

thieves, people in prison, outcasts, those who are dumb under

oppression and whose silence is heard only of God; and not

merely imagining this but actually achieving it, so that at the

present moment all who come in contact with his personality,

even though they may neither bow to his altar nor kneel before his

priest, in some way find that the ugliness of their sin is taken

away and the beauty of their sorrow revealed to them. |

|

-Carlos M. Castro |

||

|

Donate Online |

Donate By Phone |

Donate By Mail |

||

|

Click here to make an online Credit Card Contribution. All online donations are secured by GeoTrust for the utmost online security available today. |

Call us from within the United States at 1-800-325-9924 and ask for the Development Office. |

Send your check payable to teatro la fragua to: teatro la fragua Jesuit Development Office 4517 West Pine Boulevard. Saint Louis, MO 63108-2101 |

|

| ||||

|

Return to the index of

tlf news | Copyright © 2001 por teatro la fragua | |||